|

The Holy Week in Nocera Terinese and the secular ritual of the so called "vattienti" !

Thanks to the ancient Spanish influence, some of the most spectacular and touching rituals are to be found in Southern Italy.

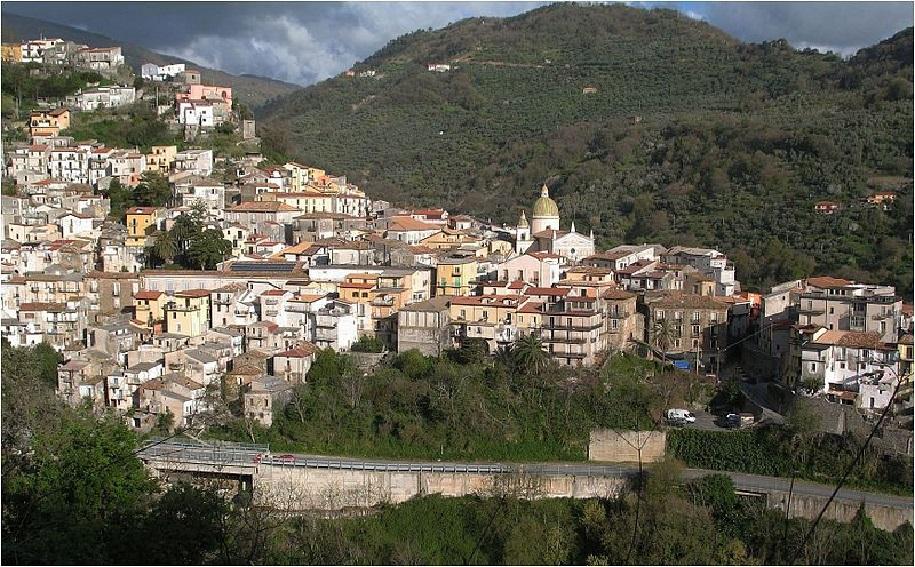

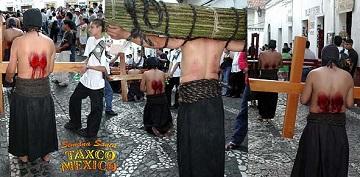

The one being re-enacted in Calabria from time immemorial is that of the Vattienti from Nocera Terinese in the province of Catanzaro, in the eyes of many, a fanatical sadomasochistic performance.

A gruesome procession with deep ancient roots, macabre and disturbing at time, that every year brings together the community of this Calabrese town.

Timely, as it has been for centuries on the occasion of Easter time, in this little town, one of Italy's most famous procession will take place.

And like every year, presumably, photographers and journalists will attend from all over Italy and abroad, together with students, scholars, enthusiasts and curious: all chasing fragments of images and emotions , even if only for a moment, that seem to come straight from another era and another time. Timely, as it has been for centuries on the occasion of Easter time, in this little town, one of Italy's most famous procession will take place.

And like every year, presumably, photographers and journalists will attend from all over Italy and abroad, together with students, scholars, enthusiasts and curious: all chasing fragments of images and emotions , even if only for a moment, that seem to come straight from another era and another time.

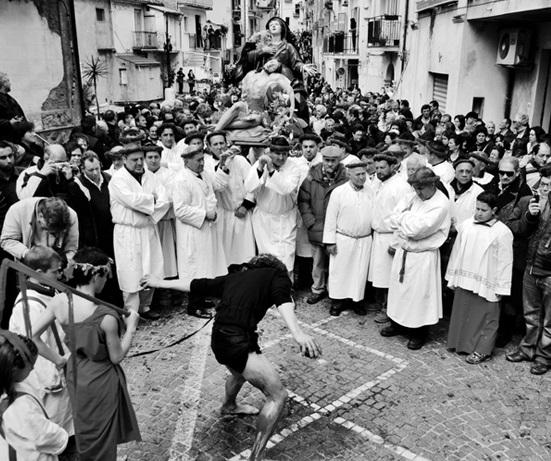

And like every year, there will be a suspicious eye and a critic who does not want to look at the real significance of this, but merely, to catalog the event as another bad memory of an illusionary past, struggling to reap the benefits of the present. The ceremony begins with the procession of  the statue of the Pieta, which depicts the dead Christ laid in the lap of the Virgin Mary. Shortly after the start of the sacred procession, the vattienti retreat to prepare for the scourging.

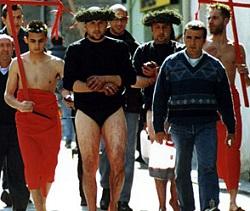

The Faithful ones dress with a shirt and dark shorts, covering their heads with a black cloth (the mannile or maccatura, the traditional headdress worn by older women Calabrese) held by a crown of thorns. Each "vattiente" is accompanied by a young bare-chested local boy, its legs covered by a red cloth, his head also surrounded by a holy thorn. the statue of the Pieta, which depicts the dead Christ laid in the lap of the Virgin Mary. Shortly after the start of the sacred procession, the vattienti retreat to prepare for the scourging.

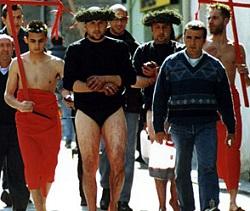

The Faithful ones dress with a shirt and dark shorts, covering their heads with a black cloth (the mannile or maccatura, the traditional headdress worn by older women Calabrese) held by a crown of thorns. Each "vattiente" is accompanied by a young bare-chested local boy, its legs covered by a red cloth, his head also surrounded by a holy thorn.

He represents l'acciomu (Ecce Homo, behold the man), the Latin words used by Pontius Pilate when he presents a scourged Jesus Christ, bound and crowned with thorns, to a hostile crowd shortly before his Crucifixion. He represents l'acciomu (Ecce Homo, behold the man), the Latin words used by Pontius Pilate when he presents a scourged Jesus Christ, bound and crowned with thorns, to a hostile crowd shortly before his Crucifixion.

The "acciomu" (young man on the left in red rope), tied to a 'vattiente' with a rope, is carrying a wooden cross covered with red cloth, the rope being a symbolic sign of communion with the Christ of the Passion.

Before heading out for the penitential procession, the vattiente prepares meticulously and disinfects the tools of his flagellation: the rose, a small disc of cork, which, once impregnated with blood will be used to leave a bloody stain on walls and doors, and the "cardo" with inserted pieces of spiked glass, to beat and bleed the legs with it.

Meanwhile, in the Quadara (copper pot) water with rosemary is boiled, with which the "vattiente" will wash its legs to increase blood circulation and then begins to strike them both with the "cardo". Meanwhile, in the Quadara (copper pot) water with rosemary is boiled, with which the "vattiente" will wash its legs to increase blood circulation and then begins to strike them both with the "cardo".

At this point, he begins his pilgrimage through the town's streets to be reunited with the rest of the faithful who follow in procession to the Pieta.

In front of the statue of the Madonna and the body of Christ, all vattienti renew the ritual of flagellation.

At the end of this touching ritual, the penitents washes the wound with water and the infusion of rosemary and wine, get dressed and join the procession.

Modern processions of hooded Flagellants are still a feature of various Mediterranean Catholic countries, mainly in Spain, Italy and some former colonies, usually every year during Lent.

For example in the commune of Guardia Sanframondi in the province of Benevento (Campania), such parades are organized once every seven years.

La Cercha is a liturgical drama that takes the Holy Friday, in Collesano, province of Palermo (Sicily).

It was staged for the first time 1667.

It is characterized by the presence of actors bearing in their hands the symbols of Passion of the Christ, like the nails and Crown of Thorns.

In addition, there are costumed actors representing Jesus carrying the cross, our Lady, the disciple John, the Holy women, the Centurion with his cohort of armed soldiers, Veronica and the angels.

|

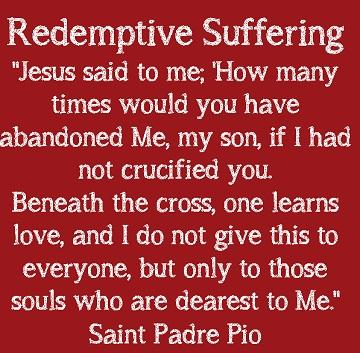

The belief is that the price that God, in Jesus, paid for the redemption of mankind, is the Passion, that is, his suffering and agony that led directly to his Crucifixion. Christians believe that, as members of the Church, they are members of the body of Jesus Christ:

Redemptive suffering is the Roman Catholic Redemptive suffering is the Roman Catholic

that human suffering, when accepted and offered up in union with the Passion of Jesus, can remit the just punishment for one's sins or for the sins of another, or for the other physical or spiritual needs of oneself or another.

Like an indulgence, redemptive suffering does not gain the individual forgiveness for their sin; forgiveness results from God’s grace, freely given through Christ, which cannot be earned.

After one's sins are forgiven, the individual's suffering can reduce the penalty due for sin.

Indulgence suffering: An indulgence, according to the Roman Catholic Church, is a means of remission of the temporal punishment for sins which have already been forgiven but are due to the Christian in this life and/or in purgatory.

This punishment is most often in purgatory .

The abuses of indulgences in the middle ages contributed to the Protestant Reformers separating from the Catholic Church.

The Church at various times sold indulgences to raise revenues. Pope Leo X (1513-1521) used the money from indulgences to construct St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

There were abuses by people like Friar Tetzel who claimed that "a soul is released from purgatory and carried to heaven as soon as the money tinkles in the box".

Martin Luther could not accept abuses like Tetzel's and started the Reformation.

Flagellantism was a 13th and 14th centuries movement, consisting of radicals in the Catholic Church.

It began as a militant pilgrimage and was later condemned by the Catholic Church as heretical.

The followers were noted for including public flagellation in their rituals.

The distinction of the Flagellants was to take this self-mortification into the cities and other public spaces as a demonstration of piety.

The movement did not have a central doctrine or overall leaders, but a popular passion for the movement occurred all over Europe in separate outbreaks.

The nature of the movement grew from a popular interest in religion combined with dissatisfaction with the Church's control.

Initially the Catholic Church tolerated the Flagellants and individual monks and priests joined in the early movements.

By the 14th century the Church was less tolerant and the rapid spread of the movement was alarming.

Clement VI officially condemned them in a bull of October 20, 1349 and instructed Church leaders to suppress the Flagellants.

They were accused of heresies including doubting the need for the sacraments, denying ordinary ecclesiastical jurisdiction and claiming to work miracles.

Flagellant orders like Hermanos Penitentes (Spanish 'Penitential Brothers') also appeared in colonial Spanish America, even against the specific orders of Church authorities.

|