|

Here, amongst nature grows the spider of madness and apathy, it insinuates itself into the blood of vulnerable bodies who know only the thankless toil of the hearth.

Here, amongst the fields of wheat and the leaves of tobacco, grows superstition.

Here, for hundreds of years the pagan genes of this land seem to have resisted the profound changes of civilization.

As a social and cultural aspect of life mainly female in nature,Tarantismo is part of the "non material" cultural heritage of the Salento and its historic and socio-economic link with Greece, the music and the dancing aspects of which live on in the local "pizzica dance", in turn related to the broad range of musical styles expressed by the "tarantelle" of southern Italy.

|

Tarantismo and the role of women in society.

Tarantismo as a phenomenon is of the same nature as women herself and the varying role that human history has imposed on her over time.

Prehistoric human beings, when they began practice worship and rituals, ascribed to the "female" in all things the nature of creator, granting women a predominant role.

The veneration of who and what directly generates life - woman and hearth - was the basis of the first forms of worship and figurative art, of which traces remain in the so called Venus of Parabita, two small female bone sculptures, valuable Paleolithic representations, evidence of the cult of the Goddess Mother, the Unique Goddess of Creation. The veneration of who and what directly generates life - woman and hearth - was the basis of the first forms of worship and figurative art, of which traces remain in the so called Venus of Parabita, two small female bone sculptures, valuable Paleolithic representations, evidence of the cult of the Goddess Mother, the Unique Goddess of Creation.

This notion of the role of women as the giver of life is also present in pre-Christian pagan civilizations, such as that of ancient Greece, in which it is already possible to identify elements of the transition from an essentially female-oriented line, linked to the cult of the Goddess Mother, to one that was strongly male-oriented, as in the Christian tradition, which attributes to the male a role of regulator and creator.

To the female, in contrast, is entrusted the role of daughter, mother, bride of God, as in the Virgin Mary.

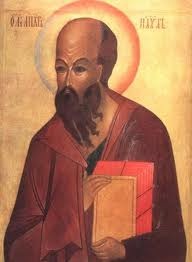

This new female identity is stated openly by  Saint Paul of Tarsus, who, in a dispute with the church of Corinth, accuses women of being distant from Christian morality, of loose morals and the fomenters of orgiastic cults; he conceives of woman as " absolute negativity and demoniac temptation". Saint Paul of Tarsus, who, in a dispute with the church of Corinth, accuses women of being distant from Christian morality, of loose morals and the fomenters of orgiastic cults; he conceives of woman as " absolute negativity and demoniac temptation".

Saint Paul also confirms the dominant role of men, arguing in the first letter to the Corinthians that " the head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man; and the head of Christ is God".

Thus woman reflects God through the mediation of man.

This theory is not arbitrary, but is required by the apostle to justify his prescriptions concerning the behavior of women in the liturgical assembly: while man, the image of God, can come into the church with his head bared, woman (who is the glory of man and his private property) must cover herself as a sign of her subjection to God mediated by her subjection to man.

In the transition from paganism to Christianity and the transformation of the numerous pre-Roman and Roman cults, the new religion created a void that could fill only by co-opting the old customs and behaviors, which were deeply rooted in many communities, in accordance with its own rules and models. Saint Paul apostle himself was aware of this.

It is on these significant aspects of transition to Christianity that the interpretation (as identified and discussed by De Martino) and historic understanding of tarantismo is based. It is on these significant aspects of transition to Christianity that the interpretation (as identified and discussed by De Martino) and historic understanding of tarantismo is based.

Tarantismo is thus descended from the concepts of pre-Christian worship, marking the transposition of the idea of "creator" from a female line to a male one and the justification of the old pagan rites in a new religion context.

It became the vehicle of a culture that survived in the subaltern world of the peasants, strongly tied to a superstitious, a critical and immature vision of Christian religion, in a geographical area living in the shadow of the church.In this perspective, the symbolism of the taranta can be seen as a way of transforming the condition of women in the Salento, on the level of their simple daily lives and on the level of their private life, intimate and hidden.

The Great Mother is universal archetype of femininity, expressed by means of collective symbolism which in tarantismo is manifested traumatically.

From the cultural point of view, the mythological and symbolic roots of tarantismo are closely connected with classical Greece.

The Acts of Congress on Tarantismo ( Atti del Convegno sul tarantismo), held in Gelatina on October 24th and 25th 1998, trace its origins to the cult of Dionysus, orgiastic god of wine, fertility and nature, key aspects in Greek mythology.

The cult of Dionysius is linked to music and dancing, for the purposes of catharsis, which was practiced in Magna Graecia (as the ancient Greek colonies in southern Italy were known) and for which the theoretical justification was provided by Archytas, Clinias, and Aristoxenus, Pythagorean scholars in Taranto. The cult of Dionysius is linked to music and dancing, for the purposes of catharsis, which was practiced in Magna Graecia (as the ancient Greek colonies in southern Italy were known) and for which the theoretical justification was provided by Archytas, Clinias, and Aristoxenus, Pythagorean scholars in Taranto. The relationship between the cult of Dionysius and Magna Graecia, particularly Taranto, would seem to be confirmed by the etymology of the term tarantismo which despite some uncertainty appears to associate Taranto with taranta and tarantola.

From both of these, the musical term tarantella is said to derive.

The ancient Greeks were the first to write extensively about the effects of animal bites and stings on humans, especially spiders, a symbolic animal in many societies, which only in this culture takes on a negative connotation, due to the sickness induced by the spider's bite and the supposed danger of contagion.

The similarities between the ritual associated with the phenomenon in the Salento and pagan rites described in the Greek mythology confirm the link between tarantismo and ancient Greece.

In the latter, for example, the rites by which the people worshipped the pagan deities were typically held in spring or during the festivities that marked the changing of the seasons, which were also the preferred occasions for the manifestations of sexual and emotional impulses, mainly on the part of the women.

The manifestations of the malaise of tarantismo also occurred at these times, and were frequent around the feast of Saint Paul in Gelatina ( June 28th and 29th).

In his Euthydemus, Plato explores the connection between the divinity by whom the victim was possessed and a particular melody corresponded to it.

He discussed the cult of the goddess of the earth and fertility and the musical therapy of the Korybantes, which entailed the exploration of various "musical moods" in an attempt to cure the possesd victim of the "telestic mania" which indicates an altered state of consciouness.

These aspects have much in common with the symbolism of tarantismo and its ritual practices, which survived for centuries, despite being assimiliated into the Christian culture.

A significant example is the concept of pathology itself, which in both the ancient Greek world and in Tarantismo is understood as a form of magic, the symbolic practices of which have miraculous powers, including that of exorcism.

|

|

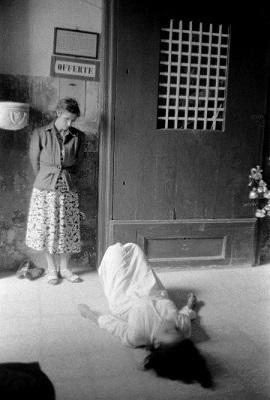

Tarantismo is phenomenon deeply analyzed through the centuries. According to the popular beliefs, it was an illness provoked by the bite of the tarantula, a small spider which was highly spread in the summer months.

It caused a state of general sickness, bellyaches, catalepsy, perspiration, palpitations and psychiatric symptoms similar to epilepsy.

The most frequent victims of tarantismo were the women since they were likely to be bitten by this spider more than other people , during the harvest.

At first, it was a religious phenomenon which characterized southern Italy and in particular, Apulia since the Middle Ages; it was very popular until the 18th century and then in the 19th century, slowly but inexorably, it faded.

As it often happens for the magic and superstitious rituals, people tried to give them a religious meaning: therefore, we can understand the role of St. Paul , considered the protector of those who were bitten by a poisonous animal and who could recover thanks to him.

The choice of this saint is not causal since according to the tradition, he himself had been bitten by a snake in Malta and survived.

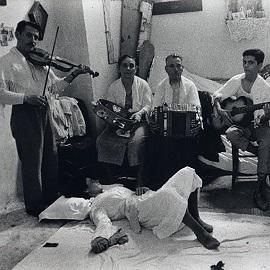

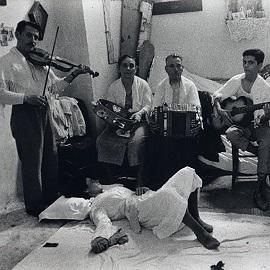

According to the popular belief, listening to the sounds of particular musical instruments (violin, accordion or tambourine) and watching certain colors (green, yellow, red) among those of the scarves waved during the rite, provoked outburst of rage that made the tarantata dance, until she fell on her back on the bed.

TARANTISM TODAY

Yet, the moments of collective participation have been progressively disappearing, and the number of people who go to church to take part in the rite is declining.

The context in which the exorcism takes place has radically changed: it is no longer the rural community gathered to share the same cultural experience, but just a crowd of curious visitors who are not involved in the rite at all.

Instead of coming by a cart, the Tarantati come by car and get out a few meters from the church entrance.

Before coming into the chapel a little rite takes place in front of the church, while the relatives of the Tarantati prevent the curious from taking photos or videos.

THE MUSIC

The extraordinary aspect of Tarantismo and of the whole Italian folk tradition is that the protagonists are all young people, whereas in many other countries the folk tradition has become something old or belonging to the past and the cultural roots have been forgotten and overwhelmed by the so called “modern” world.

Above all the teenagers are re-proposing the traditional musical repertory performing the Taranta both in the public shows and in the holy festivities.

The Taranta always seduces and leads to the difficult path, typical of youth, of finding a personal, social and cultural identity, and maybe even (like in the past) to vent all the frustrations and come back to the social order differently.

It is very common to listen to the pizzica-tarantata rhythms mixed with rap music, hip hop, house and techno music as bands like Sud Sound Sistem and Nidi D’arac usually do.

Acknowledgment :

From a study by Marta Porcino, scholar of the tangible and intangible heritage of the South. Women in the folk traditions of the Salento.

|

Saint Paul of Tarsus, who, in a dispute with the church of Corinth, accuses women of being distant from Christian morality, of loose morals and the fomenters of orgiastic cults; he conceives of woman as " absolute negativity and demoniac temptation".

Saint Paul of Tarsus, who, in a dispute with the church of Corinth, accuses women of being distant from Christian morality, of loose morals and the fomenters of orgiastic cults; he conceives of woman as " absolute negativity and demoniac temptation".

The cult of Dionysius is linked to music and dancing, for the purposes of catharsis, which was practiced in Magna Graecia (as the ancient Greek colonies in southern Italy were known) and for which the theoretical justification was provided by Archytas, Clinias, and Aristoxenus, Pythagorean scholars in Taranto.

The cult of Dionysius is linked to music and dancing, for the purposes of catharsis, which was practiced in Magna Graecia (as the ancient Greek colonies in southern Italy were known) and for which the theoretical justification was provided by Archytas, Clinias, and Aristoxenus, Pythagorean scholars in Taranto.